Five-year-old Teddy Ryder was one of the first patients to receive the “pancreatic extract” co-discovered by Frederick Banting and Charles Best at the University of Toronto. This event occurred in the summer of 1921. Teddy went on to live another 71 years with diabetes. Read more on itoronto.

A Life-Saving Discovery

Before receiving insulin, 5-year-old Teddy Ryder resembled a skeleton. Imagine a child in a wrinkled sailor suit standing in a park—this was how Toronto Daily Star described him in March 1922 under the headline “Diabetics Given Hope.” By spring of that year, as news of the insulin breakthrough emerged, Teddy’s weight had plummeted to 26 pounds. He had lost interest in everything, unable to take more than a few steps on his own.

In a letter to Frederick Banting, Teddy’s uncle—a doctor at New York’s Bellevue Hospital—described the boy’s critical health, stating he had only months to live but held out hope for a miracle.

Banting was determined to treat Teddy. Traveling to Toronto by train with his mother, the little boy received his first dose of insulin on July 10, 1922. By fall, Teddy was strong enough to return home to his family in New Jersey and begin a new life. In a letter the following year, a now-healthy six-year-old Teddy invited Banting to visit, boasting that he was “a fat boy now” who could even climb a big tree on his own.

Research and Experimental Breakthrough

Banting’s handwritten notes on the pancreas ducts and degenerating acini, leaving the islets intact, marked the beginning of his revolutionary idea. On the morning of October 31, 1920, after a restless night, Banting jotted down a 25-word hypothesis that would lead to one of the 20th century’s most significant medical discoveries. Without a lab or prior experience, Banting approached J. J. R. Macleod, a physiology professor and international diabetes expert, who agreed the idea was worth exploring if Banting committed himself entirely to the project.

On May 17, 1921, Banting and Charles Best, a physiology and biochemistry student who won a coin toss to become Banting’s assistant, began their experiments under Macleod’s supervision at the University of Toronto.

The duo spent the spring and summer of 1921 testing Banting’s theory. By August, their notebooks were filled with promising results, finally achieving a pancreatic extract that consistently reduced blood sugar levels after many failures and refinements.

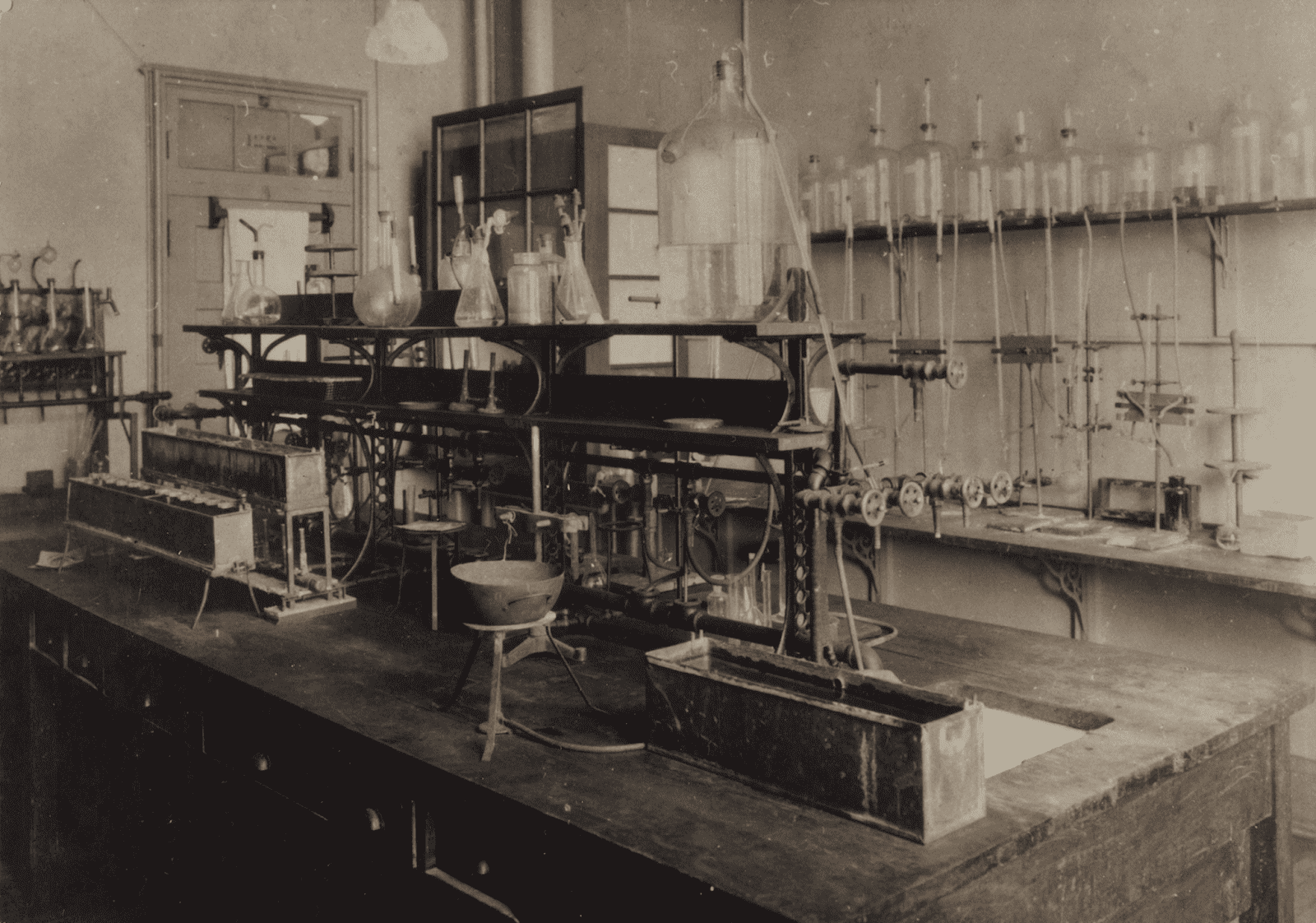

Progress continued into the winter of 1921 when biochemistry professor James B. Collip joined the team to purify the pancreatic extract, making it safe for human trials.

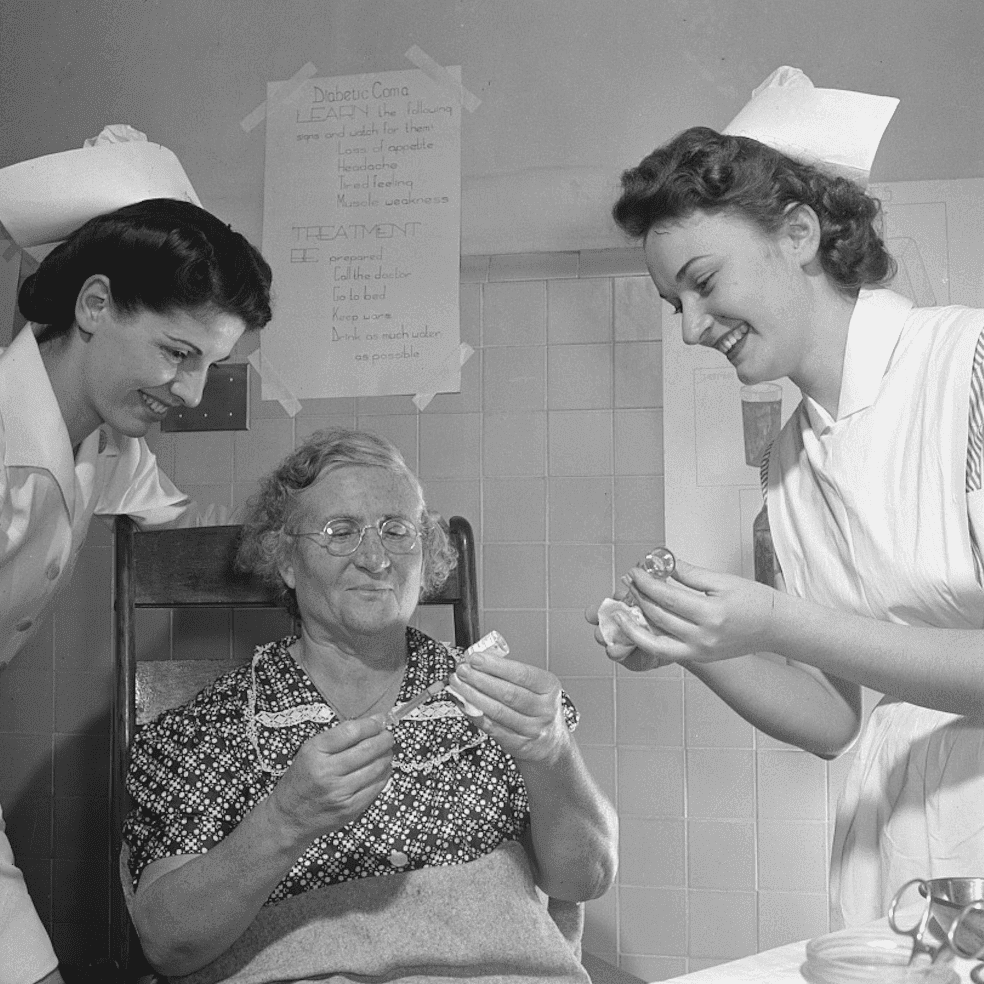

On January 23, 1922, Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old Toronto boy frequently losing consciousness at Toronto General Hospital, became the first person to receive the purified extract that would later be named “insulin.”

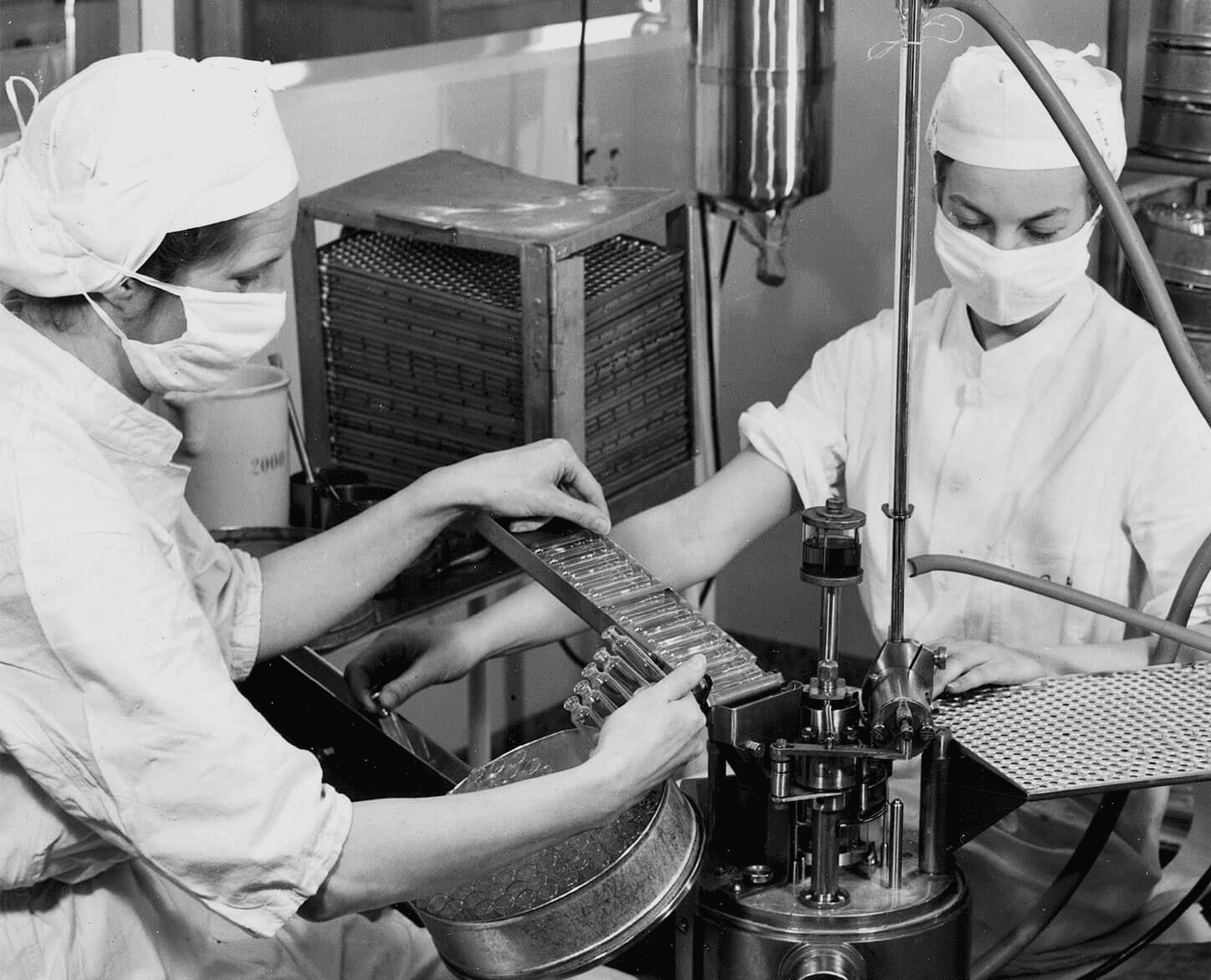

The results were extraordinary. Bill Bigelow, a young U of T surgeon who witnessed the early insulin trials, recalled seeing comatose patients seemingly brought back from the brink of death. This marked the beginning of a medical revolution. Soon after, diabetes clinics were established at Christie Street Veterans Hospital and Toronto General Hospital. The U of T Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories ramped up insulin production, and the University partnered with Eli Lilly & Co. to scale up manufacturing—moving insulin from the lab bench to hospital beds with revolutionary results.

Over the century since the historic summer of 1921, insulin has saved and improved the lives of millions of people with diabetes, both in Canada and worldwide. The discovery turned global attention to Toronto, establishing the city as a leader in diabetes research and treatment. Building on this legacy, U of T and its hospital partners have fostered a culture of discovery, innovation, and collaboration that continues to transform healthcare globally.

The Impact of Insulin Development on Toronto’s Healthcare

Building on a century of success, the University of Toronto continues to revolutionize human health through an integrated approach to healthcare research, bridging fundamental science, clinical application, and market solutions. A culture of collaboration unites researchers across diverse fields, including regenerative and precision medicine, pharmacology and drug development, molecular medicine and disease biology, mental and brain health, metabolism and nutrition, as well as global and public health systems. These areas represent just a few of U of T’s many strengths.

Toronto is home to one of the world’s largest concentrations of stem cell scientists, tissue engineers, transplantation experts, and distinguished researchers, clinicians, and physicians across all disciplines. U of T remains at the forefront of health science innovation. Currently, Toronto-based scientists are developing groundbreaking therapeutic strategies for diagnosing, treating, and potentially curing diabetes. They are also studying the relationship between the gut microbiome and Type 1 diabetes while creating a renewable pool of insulin-producing beta cells for transplantation to patients.

Innovations and U of T’s Value to the City

The revolutionary discovery of insulin in 1921 marked the beginning of a century of pioneering research and innovation at U of T, continuing to improve global health and providing individuals worldwide with the opportunity to reach their full potential. Although a cure for diabetes has not yet been found, the Nobel Prize-winning discovery of insulin remains a life-saving treatment for millions of people globally. The University of Toronto continues to lead the way in research and treatment of this condition.

In the years and decades ahead, Toronto’s researchers aim to push the boundaries of possibility, fostering the culture of ingenuity and collaboration established a century ago by Frederick Banting, Charles Best, J. J. R. Macleod, and James B. Collip. Deep learning, a revolutionary artificial intelligence technique developed at U of T, is transforming medical practices by decoding tumor DNA to identify the most effective cancer therapies for patients. Researchers are using stem cells to cure blindness in mice, developing tissue patches to repair damaged hearts, and creating miniature models of noses, mouths, eyes, and lungs.

Additionally, transformational research in Toronto focuses on improving treatments and preventing diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Scientists are pioneering novel approaches to understanding the biological causes of depression, optimizing personalized diets based on genetic profiles, and developing dietary supplements to prevent vitamin deficiencies among pregnant women, nursing mothers, and young children.