Since its founding, Toronto has faced multiple epidemics, but cholera proved to be the most devastating. The disease claimed countless lives across all age groups. Municipal authorities and doctors in Toronto made significant efforts to combat the outbreak. Learn more at itoronto.info.

What is Cholera?

Cholera is an acute intestinal infectious disease caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It spreads through the fecal-oral route, primarily via contaminated water, fruits, or vegetables.

The source of the infection is an infected person, whether symptomatic or an asymptomatic carrier. The incubation period can last up to five days. The primary symptom is diarrhea, which leads to severe dehydration, shock, and kidney failure.

In some individuals, symptoms may be mild or entirely absent. Others may experience nausea, vomiting, and muscle cramps. Without timely treatment, cholera can cause death within hours.

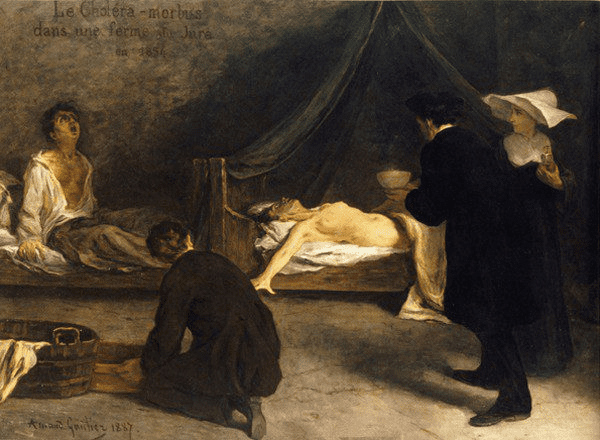

Cholera is easily treated today with oral rehydration solutions (ORS), and severe cases may require intravenous antibiotics. Unfortunately, in the 19th century, these modern treatments were unavailable. This lack of resources allowed cholera to spread rapidly across Canada, fueled by global trade and mass migration.

The Epidemic in Toronto

In 1832, cholera struck Toronto, introduced by a significant influx of European immigrants. During the spring and summer of 1832, approximately 11,000 immigrants, many unknowingly carrying cholera, arrived in the city. The disease hit with sudden ferocity, causing symptoms ranging from mild intestinal discomfort to severe and deadly outcomes. At the time, an ominous curse often heard was, “May cholera take you.”

The epidemic brought life in Toronto to a standstill. Schools and shops closed, and only businesses producing coffin boards experienced growth.

Since cholera spread through contaminated water and food, quarantine was the only effective measure to curb the disease. To manage the crisis, municipal authorities established a Board of Health and a quarantine station on Grosse Isle.

The Board of Health’s responsibilities included setting up lazarettos (quarantine hospitals), hiring doctors, and providing treatment to the sick. Residents were instructed to report to lazarettos at the first signs of illness. However, fear prevented many from seeking medical help.

The first cholera epidemic ended in the fall of 1832, but the disease persisted among new immigrants and Toronto’s 5,500 residents.

To curb the spread, the city implemented strict restrictions. Boats were prohibited from docking, and immigrants were barred from entering the city. Armed guards were stationed at some roads to prevent strangers from passing through.

Fear of infection was so overwhelming that, in some cases, families refused to bury their dead. Bodies of cholera victims were often placed in shacks and burned.

Property owners were ordered to disinfect their homes with limewash and whitewash their buildings. If a cholera victim had died in a residence, the house was burned down. While lime was distributed for free, compliance was low, prompting authorities to introduce fines for noncompliance.

Ships bound for Toronto were inspected at river mouths. Many captains, unwilling to have their vessels labeled as “infected,” frequently ignored regulations.

Over time, it became clear that preventing cholera required providing access to clean water. Effective treatment involved basic rehydration techniques. While these insights emerged too late to save many lives during the 1832 outbreak, they shaped future public health strategies, emphasizing sanitation and proper water supply.