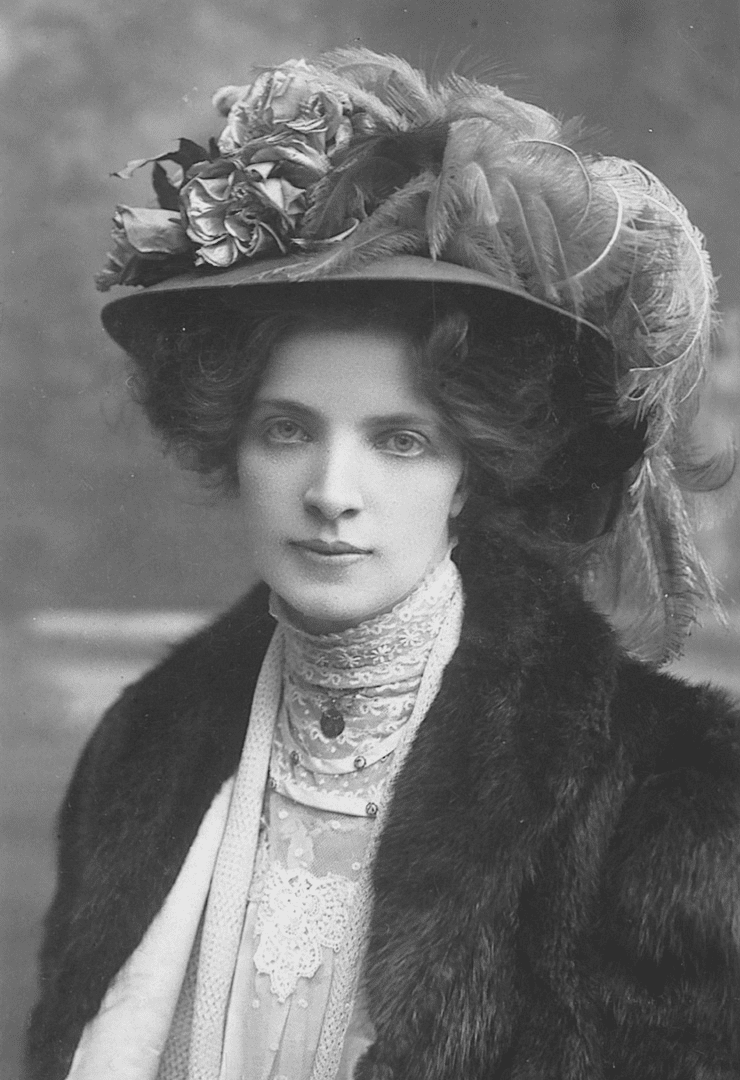

Maud Allan was a renowned dancer on London’s West End stage in the early 20th century, captivating audiences across Europe with her confident and alluring performances. How did she become entangled in one of the most sensational trials of the century? This is a complex tale of treason accusations, a libel case, and unapologetic female sexuality. The controversy even led to a public trial. Heightened paranoia during World War I meant that non-conformists were often seen as a threat to national security. This court case not only tells a fascinating story but also sheds light on the tensions of the time. Read more on itoronto.

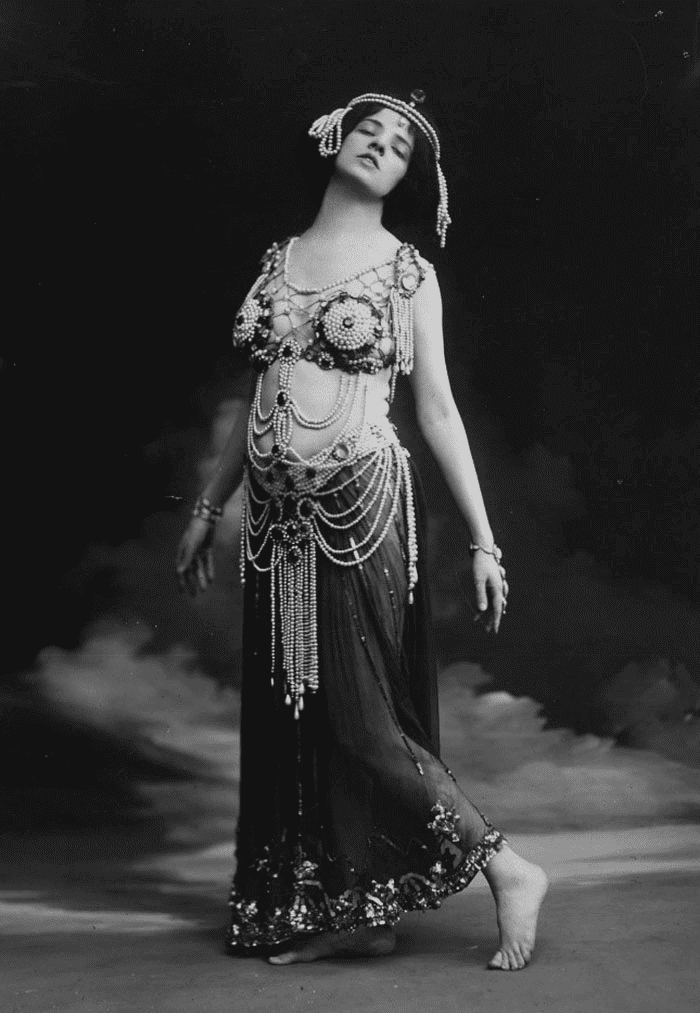

Allan as Salome

Maud Allan was born as Ulla Maud Durrant in Canada around 1873. In her twenties, she moved to Europe to escape a dark family history—her brother was convicted of a gruesome double murder in San Francisco. Allan initially trained as a pianist before stepping onto the stage and remarkably rebuilding her fortune and reputation.

By 1906, she had gained public attention in Vienna with her rendition of Salome, based on Oscar Wilde’s controversial play. Salome is a biblical figure who, according to legend, danced before King Herod while holding the head of John the Baptist on a silver platter. Wilde’s version features Salome kissing John’s severed head, solidifying her as a symbol of dangerous and wanton womanhood. Allan became famous for her seductive interpretation of the iconic Dance of the Seven Veils, for which she designed her own provocative costumes. This role was Allan’s first perceived misstep: portraying a sexually confident woman on stage. The second was her association with Wilde, whose 1895 trial for gross indecency had scandalized the public. At the time, there were strict rules regarding religious depictions on stage, let alone ones as controversial as Salome.

Private Theatres and Accusations of Immoral Roles

Allan’s performances toured Europe and beyond, culminating in a highly successful run at London’s Palace Theatre beginning in 1908. By 1918, she reprised the same confident role while collaborating with Dutch impresario J.T. Grein, who was instrumental in transforming London’s West End. Grein founded the Independent Theatre Society, cleverly avoiding censorship by holding “private” subscription-only performances.

Grein himself had controversial ties, particularly as a promoter of works from mainland Europe. In 1900, he founded the German Theatre in London program, which brought him little favour amid the anti-German sentiment of World War I.

Allan’s Salome performance in 1918 was not public but instead staged as a closed, unlicensed event. To attend, audiences had to apply via Miss Valletti at 9 Duke Street, Adelphi W6. This arrangement circumvented the censorship of the Lord Chamberlain, who had banned Wilde’s works following his trial.

Noel Pemberton-Billing, a British inventor, writer, and Member of Parliament, was also a staunch right-wing activist. He founded the Vigilance Society during World War I, with its newspaper The Vigilante claiming to uphold the “purity of public life.” Pemberton-Billing used the publication to criticize Allan’s Salome performance. He implied that Allan was a lesbian and part of a “cult” of women attracted to the same sex. While relationships between women were not illegal (unlike male homosexuality), they were socially taboo and sparked controversy.

Pemberton-Billing went further, accusing Allan of having a romantic relationship with Margot Asquith, wife of former Prime Minister H.H. Asquith. He suggested that Allan’s private Salome performances would attract high-profile homosexuals whose names, he alleged, were recorded in the so-called “Black Book.” This book, he claimed, listed 47,000 individuals supposedly being blackmailed by the German government.

Maud Allan’s Libel Trial Against Pemberton-Billing

The broader context of the trial is crucial. Amid World War I, society sought scapegoats. Allan, portrayed as a sexually deviant foreigner who had studied music in Germany, became an easy target. Pemberton-Billing argued that homosexual individuals were vulnerable to blackmail, which he saw as a wartime liability. Despite frequent mentions of the “Black Book,” no such evidence was ever presented.

Fearing the accusations would ruin her career, Allan sued Pemberton-Billing for libel. The trial, which lasted six days, garnered significant public attention. The National Archives contain records of the trial, including Home Office files and correspondence regarding unlicensed plays of the era. One file includes a copy of The Vigilante from June 1918, featuring a biased account of the case.

During the trial, Pemberton-Billing claimed ignorance of the phrase “cult of the clitoris,” which he had used to describe Allan. When questioned about the defamatory term, Allan responded, “Gentlemen, I refuse to soil my tongue by repeating what those words mean.” Meanwhile, Allan admitted to knowing little about Salome but described Wilde as “a great artist.”

The judge, rather than focusing on the libel accusation, seemed more concerned about the unlicensed play being staged at all. In his closing remarks, he noted that Allan’s costume was “better than appearing in nothing at all.”

The Verdict

The jury found Pemberton-Billing not guilty, prompting cheers from the courtroom gallery. In his closing speech, the judge heavily criticized the play, stating it was unsuitable for public or private performance. Wilde, Salome, and Allan faced public humiliation, while Pemberton-Billing was acquitted.

The trial’s wider significance can be seen in letters to the Home Office and Cabinet documents of the time. Government officials speculated on how the case might influence perceptions of lesbianism. Did Pemberton-Billing, despite his conservative stance, inadvertently raise awareness of a “cult” of women? Reverend Francis Knight wrote to the Home Office during the trial, urging judges to dismiss the case to avoid further publicity in the nation’s interest.

Though Allan vehemently denied Pemberton-Billing’s accusations, it is worth noting that Margot Asquith supported Allan financially until the death of H.H. Asquith in the late 1920s. Moreover, Allan lived with her secretary and lover, Verna Aldrich, in a Regent’s Park apartment funded by Asquith.

Sources