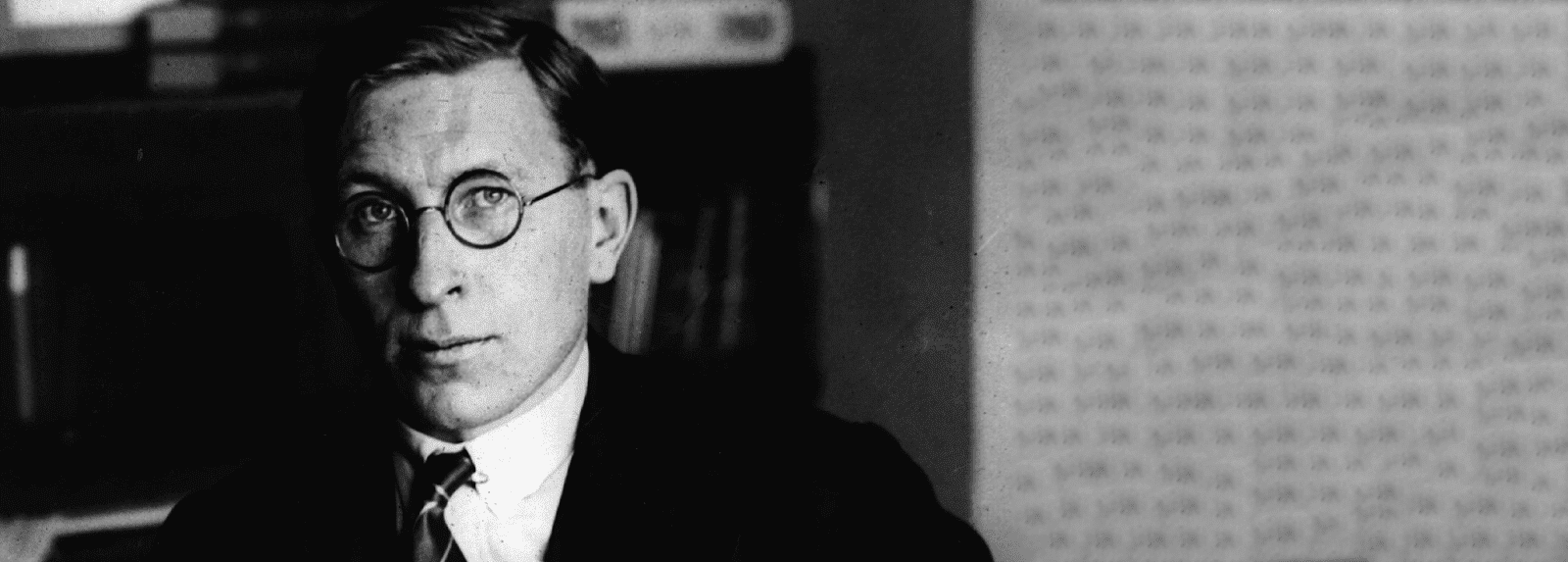

Frederick Banting changed countless lives by following his heart’s calling to become a physician. Today, we’ll explore the early life of this Toronto-born genius and his groundbreaking experiments. More on itoronto.

Early Life of Frederick Banting

Frederick Banting was born on a farm near Alliston on November 14, 1891, as the youngest of four sons of William Thompson Banting. A diligent and serious child, Frederick excelled in school. His teachers described him as hardworking and reserved. These qualities earned him admission to the University of Toronto.

In 1910, Banting enrolled in a general arts program at Victoria College with plans to pursue a Methodist ministry. However, this decision was more reflective of his parents’ wishes than his own, and he left Victoria College before completing his first year. By fall 1912, Banting had redirected his ambitions toward medicine and enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto, specializing in surgery.

Banting’s Military Service

After World War I was declared on August 4, 1914, Banting attempted to enlist in the Canadian Army the following day. Due to poor eyesight, his application was initially rejected. Later, however, he joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps, excelling in his studies and completing most of his medical training. He enlisted as a private in spring 1915 and was promoted to sergeant by fall.

The University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine, eager to support the war effort, created an accelerated program for the Class of 1917, condensing the fifth year into summer and fall terms. On December 9, 1916, Banting received his Bachelor of Medicine degree alongside his classmates and reported for military service the next morning.

Initially stationed at Granville Hospital in England, Banting was deployed to the front lines in June 1918 as a battalion medical officer. In late September, he was wounded at the Battle of Cambrai, where his courageous actions during the assault earned him the Military Cross. Although his injury was not severe, it healed slowly, keeping him in the hospital until December 4, 1918—more than three weeks after the war ended. He resumed his duties as a medical officer in England and later at Toronto’s veterans’ hospital after returning to Canada in spring 1919.

Banting was demobilized in summer 1919 but remained in Toronto for a year to complete his surgical internship at The Hospital for Sick Children. By 1920, having served as senior resident surgeon, Banting planned to establish his own practice and moved to London, Ontario. However, a lack of patients and financial difficulties led him to accept a part-time position as a demonstrator at the University of Western Ontario’s medical school.

The “Idea” That Transformed Lives

On the night of October 31, 1920, while preparing a lecture on the pancreas, Banting had the “idea” that would change not only his life but also the lives of countless others. He initially approached Dr. F.G. Miller, a medical researcher at the University of Western Ontario, who referred him to Professor J.J.R. Macleod, a leading carbohydrate metabolism expert at the University of Toronto. Despite Macleod’s skepticism about Banting’s procedure, he provided him with laboratory space, dogs, and an assistant.

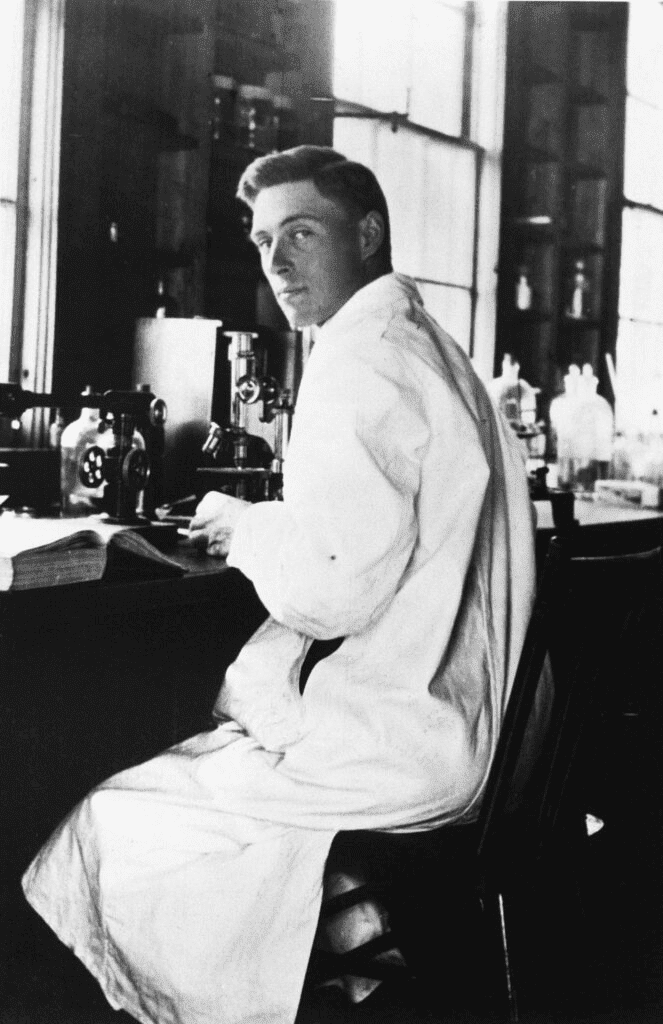

Banting returned to the University of Toronto to begin his experiments. He collaborated with Charles Best, who specialized in physiology and biochemistry. Initially, Banting focused on surgeries while Best measured blood and urine sugar levels. Over time, both men became proficient in each other’s tasks. Their meticulous observations and calculations were recorded in a series of notebooks.

The Discovery of Insulin and Founding the Diabetes Clinic

After months of challenging experiments, including difficulties with pancreatic procedures and the loss of test dogs to infection, their persistence paid off. On July 30, 1921, Banting and Best successfully administered a pancreatic extract to a diabetic dog, significantly lowering its blood sugar levels. Encouraged, they continued refining their methods.

In November 1921, Banting and Best presented their preliminary findings at the University of Toronto’s Physiological Journal Club. Shortly after, they began working on a long-term experiment using a diabetic dog named Dog 33, which required continuous insulin injections. In December, biochemist J.B. Collip joined the team to purify the extract further.

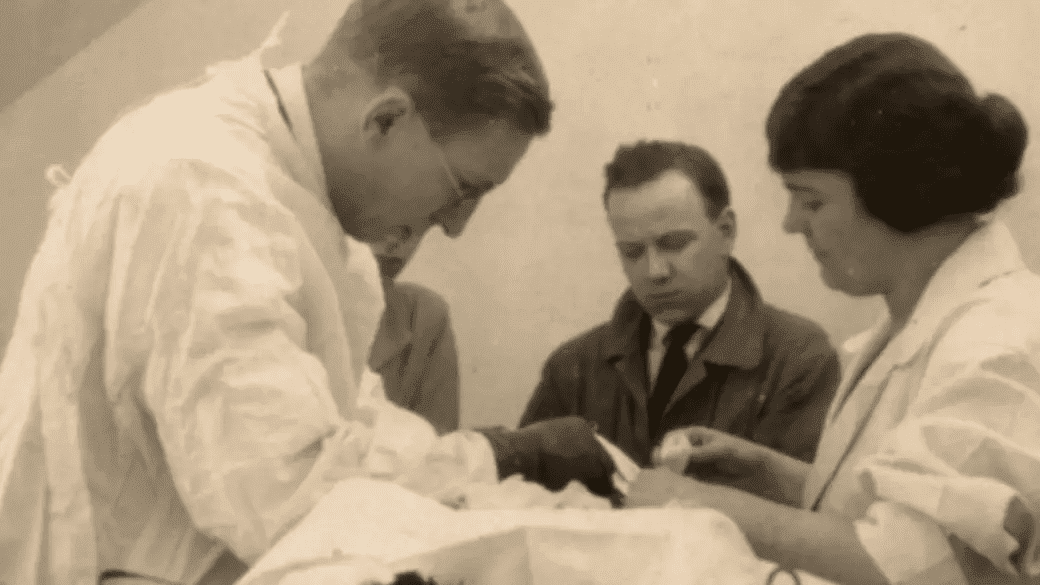

However, the Toronto team was not discouraged: by late January, Collip’s purified extract was successfully administered to the first human patient, Leonard Thompson. This pivotal moment involved collaboration with experts at Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories, who contributed to the development and production of the pancreatic extract. Banting’s direct involvement in experimental work during the winter and spring of 1922 is less documented, yet he continued to treat diabetes patients as insulin became more accessible.

Around April 1922, with the support of Dr. Joseph Gilchrist and the Department of Military Civil Rehabilitation, Banting established a diabetes clinic at Chrystie Street Hospital. He also opened a private practice at 160 Bloor Street, where he treated private patients, including Jim Havens from Rochester, New York—the first American citizen to receive insulin treatment.

Following the groundbreaking discovery of insulin, Banting led significant research on silicosis, although he never again achieved a breakthrough of similar magnitude. Nevertheless, he earned his Doctor of Medicine degree, further solidifying his legacy in medical history.