Medical theory and practice in Toronto evolved significantly from the 16th to the 20th century, driven by advancements in medical education, regulation, anatomical knowledge, public health, immunization, and pharmacology. Toronto’s medical research contributed to breakthroughs in anesthesiology, neuroscience, and the treatment of diabetes, polio, malaria, heart disease, and tuberculosis. This article delves into the development of medicine in Toronto. Read more on itoronto.

Indigenous Medicine

Medicine in Toronto began centuries before French settlers arrived in North America. However, as Indigenous knowledge was transmitted orally, written records of their practices and beliefs were left by European explorers and settlers. Indigenous peoples often sought healing from shamans or medicine people, using effective herbal remedies like wintergreen oil, highbush cranberry, and loofah plants, as well as physical treatments such as sweat lodges and massage therapies. For example, the Indigenous peoples taught Jacques Cartier’s expedition about a remedy for scurvy—a tea made from white spruce bark and branches—that saved many lives.

These systems of medicine began to erode following prolonged contact with European settlers, who brought epidemics such as measles, typhoid, diphtheria, and smallpox. These diseases devastated Indigenous communities, leading to a gradual decline in traditional medical practices.

Medical Regulation in Canada and Its Impact on Toronto

In the late 18th century, attempts to regulate the medical profession sparked debates between universities and licensing boards over whether a medical degree was equivalent to a license to practice. The rise of charlatans and unqualified practitioners led to public preference for these alternatives due to a lack of trust in formally trained doctors.

Licensing authorities were established in Upper and Lower Canada by the late 1800s. In Lower Canada, a governor-appointed council was created under British parliamentary law to prevent unlicensed individuals from practicing medicine. However, tensions between French- and English-speaking doctors delayed further definitions of the profession until the creation of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Lower Canada in 1847.

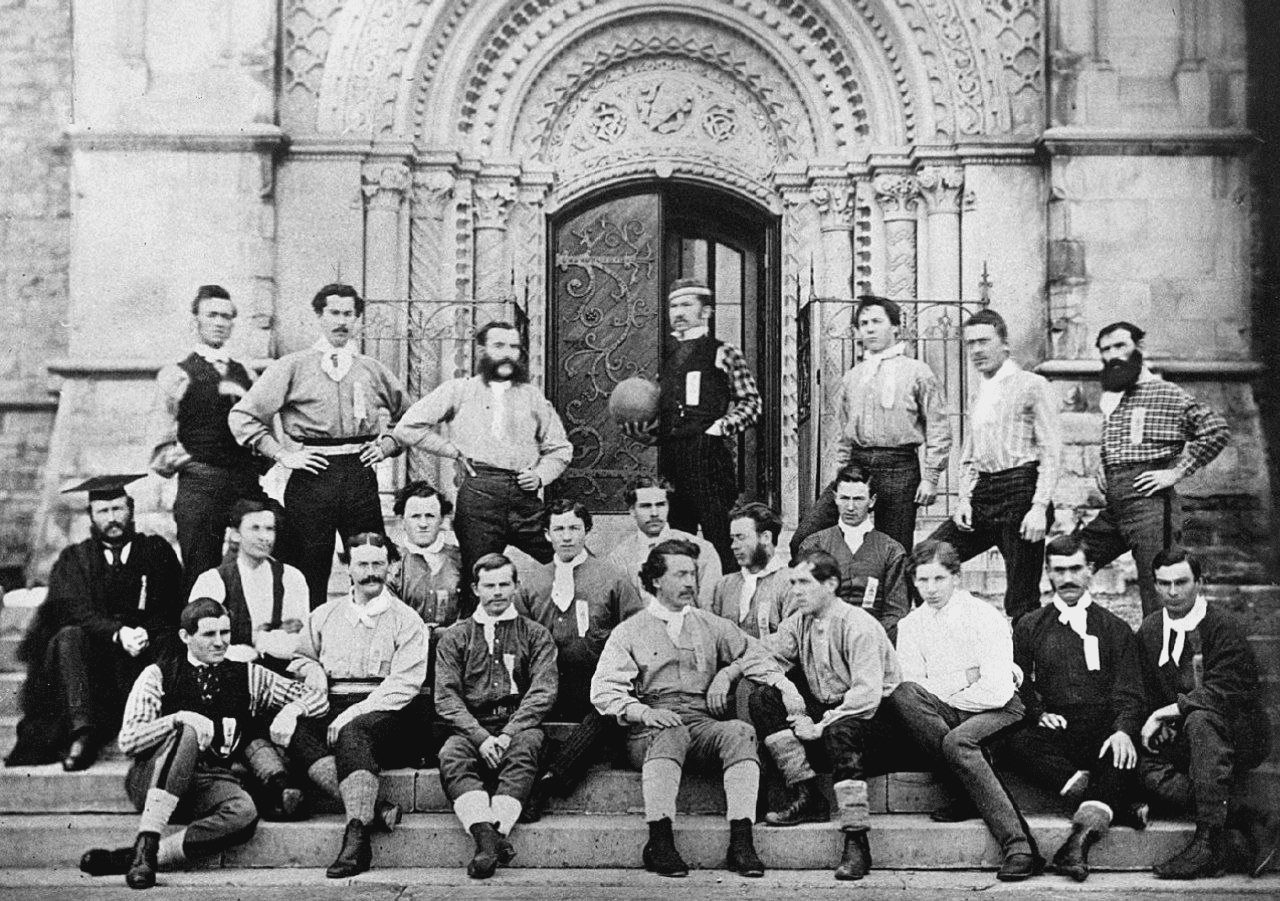

In 1849, amendments to the Incorporation Act provided automatic membership in the College for practitioners active in 1847. In 1839, a group of Toronto physicians, many of whom had trained in Britain, was registered as the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Upper Canada. However, the act to incorporate this College was rejected in 1840. In 1869, the Ontario Medical Act formally established the new College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, granting it authority to examine prospective practitioners and university graduates.

In 1867, the Canadian Medical Association was founded, marking a significant milestone in the regulation of the medical profession. The mid-19th century was a turbulent time for Canadian medicine, marked by tensions between English- and French-speaking physicians, as well as between those trained in Toronto and those educated in other Canadian cities. These conflicts underscored the growing pains of a profession striving for coherence and professionalism across the young nation.

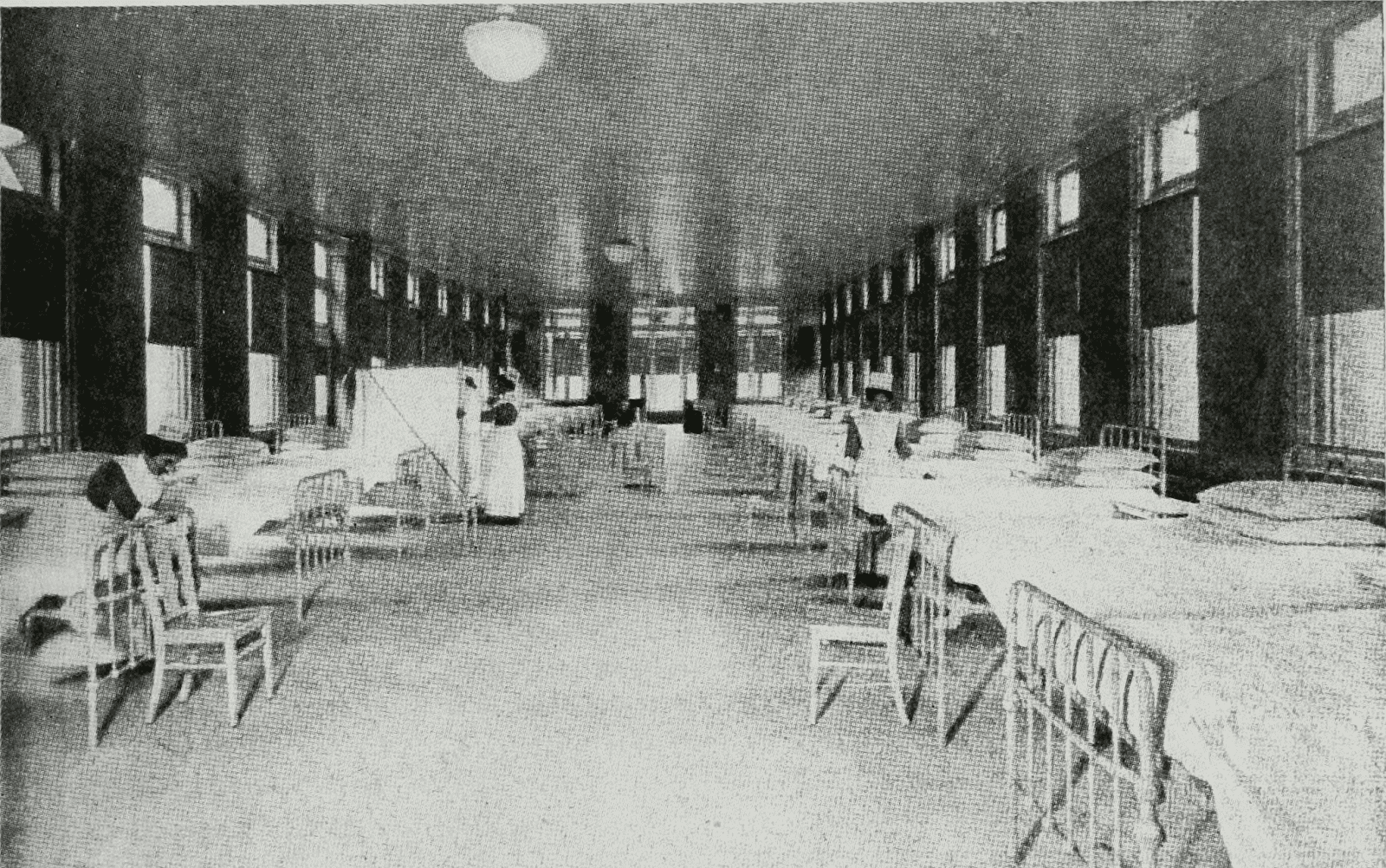

Epidemics and Public Health in Toronto

As Toronto’s population grew, the city became increasingly vulnerable to epidemics. Cholera outbreaks in 1832, 1834, 1849, and throughout the 1850s devastated the city. The 1832 outbreak spread rapidly from Quebec City to Upper Canada within three weeks. During these years, Toronto physicians debated whether cholera was contagious. Many considered it a blood disease, prescribing treatments such as bloodletting, opium, and mercury-based calomel. In 1854, Italian scientist Filippo Pacini identified the cholera bacterium under a microscope, but his findings were largely ignored until germ theory, championed by Louis Pasteur, gained acceptance in the following century. German researcher Robert Koch independently identified the cholera and tuberculosis bacilli in the 1880s.

Although the connection between microorganisms and disease was not fully understood in the 19th century, Toronto officials implemented sanitation laws to protect public health. As early as 1834, William Kelly, a surgeon in the Royal Navy, suggested a link between clean water and disease prevention. Local health boards were established to enforce quarantine and sanitation measures. By the late 19th century, public health efforts included laws restricting immigration, ensuring food safety, and improving sanitation. Resistance to these measures was strong, especially regarding mandatory vaccination. While a smallpox vaccine was introduced in Toronto in the early 1800s, epidemics continued into the 20th century until vaccination’s effectiveness was widely acknowledged.

Women in Medicine During the 19th Century

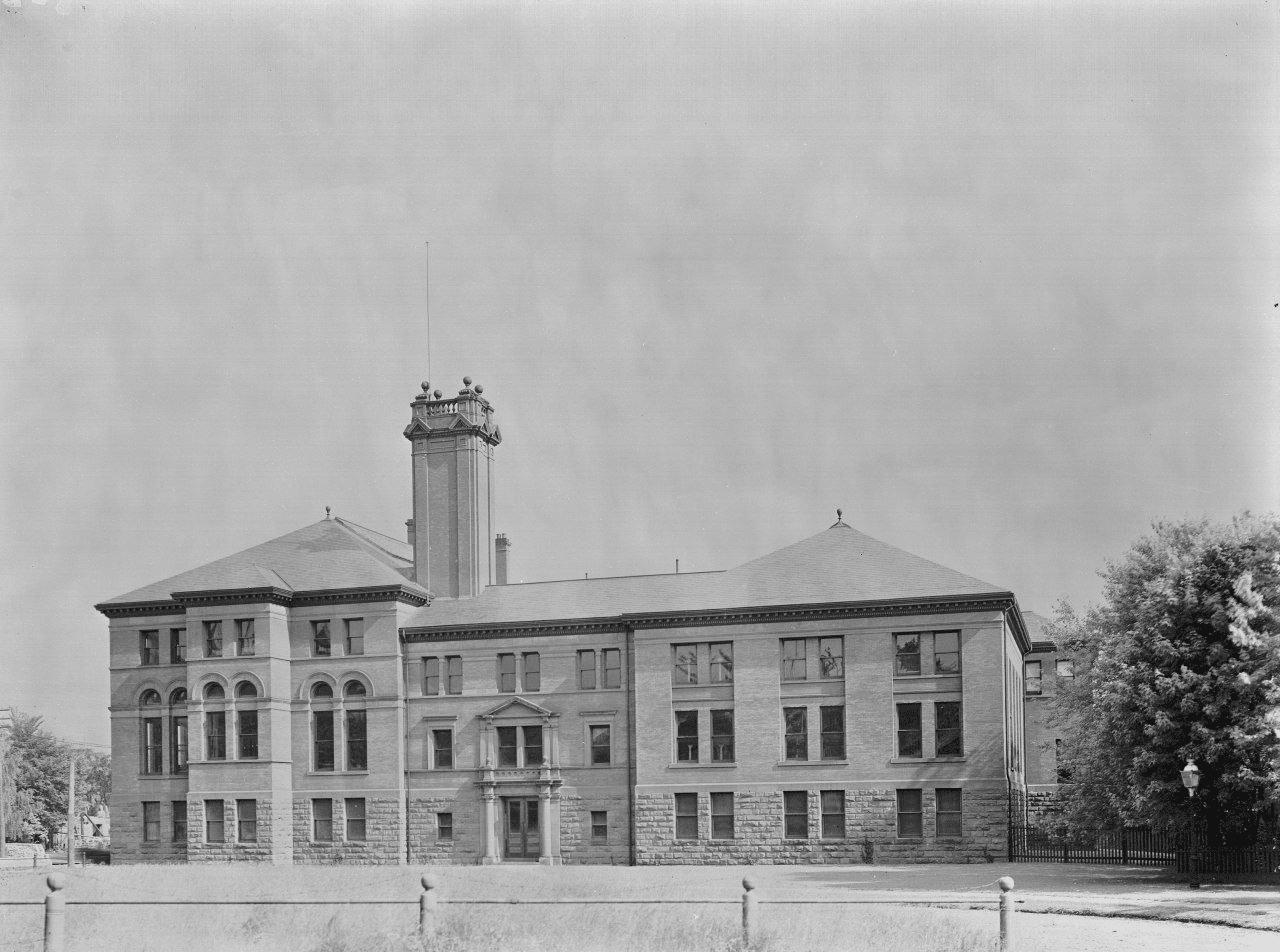

By the 1850s, women began demanding access to medical education. However, most early female physicians, such as Emily Howard Stowe and Jennie Kidd Trout, trained outside Canada. In 1883, the Woman’s Medical College opened, affiliated with the University of Toronto and Trinity College. These institutions offered coursework but did not grant degrees. By 1895, students from the Ontario Medical College for Women could sit for examinations at other medical schools. Dalhousie University (1890), the University of Western Ontario (1890s), and the University of Manitoba (1891) soon followed suit. However, McGill University and universities in Laval and Montreal only opened their doors to women much later. Early female practitioners, including Elizabeth Matheson and Maude Abbott, made significant contributions to Toronto’s medical landscape.

20th-Century Medical Achievements in Toronto

Toronto’s early medical research culminated in the groundbreaking discovery of insulin in 1922 by Frederick Banting, Charles Best, and J.J.R. Macleod. This achievement, alongside the growing interest in medical research, spurred government funding and the establishment of numerous research institutes.

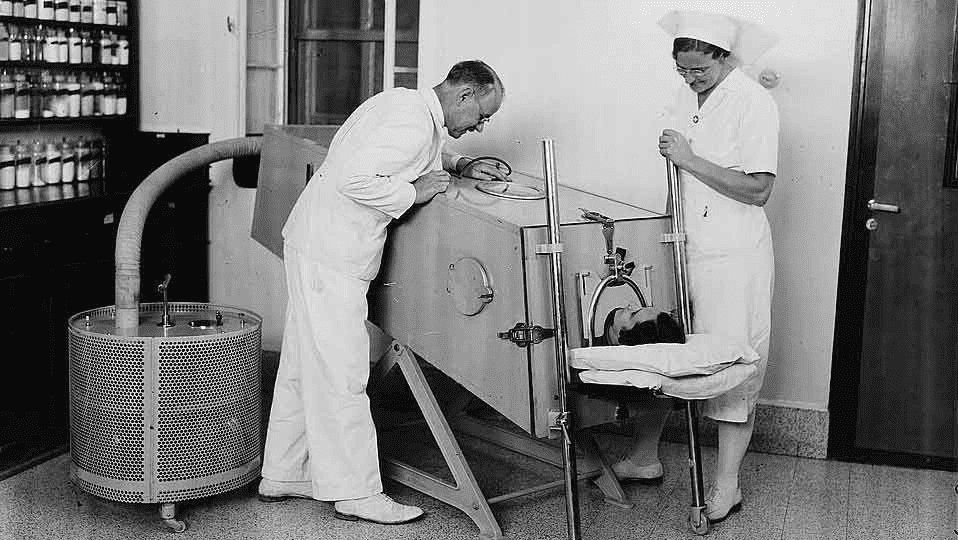

With the approach of World War II, medical practice shifted to focus on immunization, which helped control several severe diseases. Improved diets, public health measures, and more competent hospital care contributed to overall better health outcomes. Surgical procedures became more advanced, with higher success rates. The discovery of sulfonamide drugs in the 1930s and the mass production of penicillin in the 1940s revolutionized the treatment of bacterial infections. In the early 1950s, a vaccine developed with contributions from Toronto’s Aventis Pasteur Limited effectively eradicated polio, marking a significant milestone in global healthcare.